First Poem, Best Poem

Layla Benitez-James

May 07, 2013

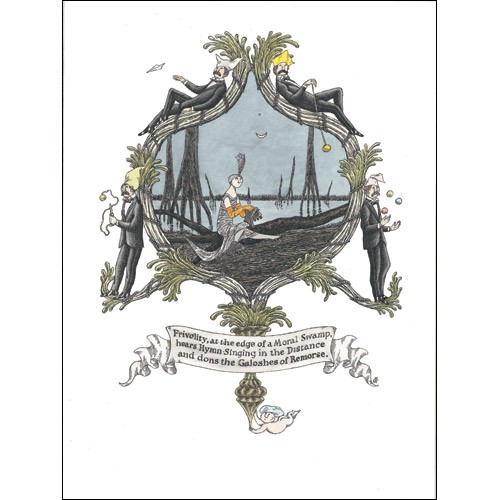

I find myself standing a little ways away from my lectern, staring off into space and picking at my lips with bitten-short fingernails. This happens every once in a while when I am working--I find that I unconsciously drift away physically from my workspace when I am drifting off mentally. At times this temporary avoidance is more productive than spacy; I will vacuum, or begin an excavation of my sink, thinking, from one of those writer lists, that "all work is the avoidance of harder work." Currently in the Penelope-esqe exercise of composing a manuscript, I'm attempting to organize the poems I have written over the past years into a cohesive collection. In our master class we have talked about the various ways to order a manuscript: the chronological, the narrative, the thematic, the formal, the random, gut-level, etc. I had around eighty pages when I began whittling the work down. I think about chronology: impossible, I have no clue when some poems were written. I think about narrative but there is no consistent speaker and this would force me to thematically group my poems; there is only so long someone wants to spend in the death section of a manuscript. I ask Google if there is a website that will alphabetize a list for me: of course there is. It gives an interesting kind of order but must be discarded as well. I return to a favorite Edward Gorey sketch I have put on several tea trays, a kind of patron saint of mine.

"Frivolity, at the edge of a Moral Swamp, hears Hymns Singing in the Distance and dons the Galoshes of Remorse."

I think back to when I first began reading collections, and what knocked my socks off. I think about the poet Jack Myers. I only studied with him for two weeks in Prague, but he left a deep impression and gave me the phrase "knocked my socks off" to use for collections that wowed me. A friend recently gave me Myers's The Portable Poetry Workshop which has a wonderfully helpful and succinct breakdown of "Structuring a Manuscript," but formal knowledge seems to fall by the lecternside when I attempt to work with my own poems and worry how they will speak to one another. Ultimately, I have to take to the floor, marked-up printouts cast and recast into piles so I can imagine one beginning line coming after some end line, and how the poems will speak to each other.

I have become especially nervous about first and last poems and how they define the rest of the work. I know that when I pick up an unknown collection I flip to first and last to judge. I have found myself, when I have my wits about me, at my bookcase, excusing myself from the harder part of the work to "research," and see how those I admire weave their work together.

I have been taking stock of the lines which lead us into and out of a book, and why not? We humans take entrances and exits extremely seriously; we comment over the weak handshake; we learn the correct number of kisses for different countries; we are hurt when a loved one does not kiss us before leaving. In fiction this conversation is alive and kicking. There are countless lists which float around and offer up some of the best.

I remember, after seeking refuge from a rainstorm in his warm and empty restaurant tucked in a little alley in Oporto, Portugal, getting into an argument with a man about the opening lines of Mrs. Dalloway. I was drinking white port and we were smoking inside because of the rain. I had bought a Portuguese translation, A Festa de Mrs. Dalloway, and he had asked me if I could read Portuguese. I explained that the novel was so familiar to me, a favorite, that it was helping me to learn. He liked this. He pointed to a word--luvas--and asked what it was. In my head ran "Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself," and I said, "flowers."

Confusion followed, he shook his head and I repeated "flowers" in the three languages I knew it in. We spoke with our hands a bit; he made a fist and let his other hand push through and open, I nodded, "flower, or bloom maybe," I thought it must be some slight variation. It was not. In this version, Mrs. Dalloway says she will buy the gloves herself. Our argument flowed from the fact that he believed it did not matter what she bought, as long as it did not affect the plot, the action, of the novel. For me, the first line was sacred. We never agreed.

Clarissa clearly not carrying a bouquet of gloves.

In poetry, this conversation is not fully there. There are lists of the best lines in poems, or of the most poignant opening lines, but not with the collection in mind, not as the opening line speaks to the entrance into the poems as a whole. I think of when I learned about stanzas and the fact that the word is also Italian for "room." I was taught to think of stanzas like little rooms of a poem that you are led through by the poet. I realized in looking at these first, and then last, lines of collections that they are often memorized, carved into my brain from reading them so often.

|

Comments (0)

Add a Comment